By it admin

Did you know a single cotton T-shirt may require up to 700 gallons of water and may travel across several countries during production before it ends up in your closet? Stop and soak that in for a second. T-shirts are one of the most tossed items that end up in landfills, where an estimated 50 million tons of clothing are discarded every year, and most of it does not biodegrade, as most landfills are not set up to create a conducive environment to facilitate biodegradation. Athletic footwear is another often-used clothing item and according to the U.S. Department of the Interior, Americans throw away over 300 million pairs of shoes every year that end up in landfills, and it takes 30 to 40 years to decompose. Most sneakers are made up of at least a dozen plastic parts—from plastic, to rubber, to glues—that can make it almost impossible to truly disassemble and recycle and it can take up to 1,000 years to break down, eventually degrading into tiny plastic particles that make their way into the soil and ocean (and eventually our bodies).

When a t-shirt costs the same as a Starbucks latte and shoes are not super expensive either, people often don’t think twice about buying regularly and discarding often and it is no surprise that the fashion industry is one of the largest polluters in the world, alongside oil and transportation, agriculture, residential and commercial cooling, heating and waste management, and other industries.

One garbage truck of textiles is sent to the landfill every second. This is an estimated $500 billion value lost every year due to clothing being barely worn and rarely recycled. If nothing changes, by 2050 the fashion industry will use up a quarter of the world’s carbon budget. Washing clothes releases half a million tons of plastic microfibers into the ocean every year, equivalent to more than 50 billion plastic bottles.

So, how did we get here?

Our current global economy has been rapidly advancing since the industrial revolution in 1684 when Thomas Savery invented the steam engine. And that changed everything. This invention kick-started the industrial revolution, which transformed our ability to make things. Raw materials and energy were seemingly infinite, and labor was readily available. For the first time in history, goods were mass produced. But today, we have to stop and think of the word “finite” for a bit.

A Take-Make-Waste Model

“We have been perfecting a linear economy for 150 years. Where we take a product out of the ground, make something from it, and after using the item for a brief period, we throw it away. What we have out there is all we have. There is no more,” said Ellen MacArthur, a retired English sailor who broke the world record for the fastest solo circumnavigation of the globe in 2005 and launched the Ellen MacArthur Foundation after, a charity that works with businesses and education institutions to accelerate the transition to a circular economy.

And our current global economy is no different. It is entirely dependent on finite materials. And the fashion industry in particular is a linear economy—takes resources from the ground to make products, which are then used and tossed. It is a take-make-waste model. How we manage resources, how we make and use products, and what we do with the materials afterwards is the only way we create a thriving economy that can benefit everyone within the limits of our planet.

“If you look at material volatility, you begin to realize you want to buy less, use less, do less. It seems like doing less is what you have to do for the global economy to work in the long run. But even with that, you realize that the system itself in where we live is fundamentally flawed. When you look at our operating systems, you realize to make complex changes, you have to look at multiple inputs. Our global economy cannot run in the long run the way it is going right now,” said Ellen MacArthur in her TED Talk in 2015.

Recycling and Upcycling

According to the United States Environment Protection Agency (EPA), the main source of textiles in municipal solid waste (MSW) is discarded clothing. The EPA estimated that the generation of textiles in 2017 was 16.9 million tons and that figure represents 6.3 percent of total MSW generation that year. The recycling rate for all textiles was 15.2 percent in 2017, with 2.6 million tons recycled. The total amount of textiles in MSW combusted in 2017 was 3.2 million tons. Landfills received 11.2 million tons of MSW textiles in 2017. This was 8 percent of all MSW landfilled. Recyclers like Goodwill keep approximately 3.8 billion pounds of post-consumer textile waste (PCTW) out of the landfills. On average, US citizens throw away about 70 pounds of clothing and other textiles each year.

A recent Vogue article, The Future of Fashion Is Circular, talked about how a more sustainable fashion industry depends on using what exists, eliminating the problem of clothing in landfills, and reframing the way we value our garments—or known as closed-loop companies, where worn out items will be recycled or upcycled, with nothing wasted in the process. This increasing interest in sustainable fashion, resale market, the health of the environment, and overall ethical practices in businesses and consumption recently has been mostly driven by Millennials and Gen Z, who were identified as adopting secondhand fashion 2.5x faster than other age groups in the 2019 Resale Report by ThredUp and dedicated to reducing their carbon footprint by actively participating in the circular economy.

The Circular Economy is More Than Recycling. And More Than Sustainable Fashion.

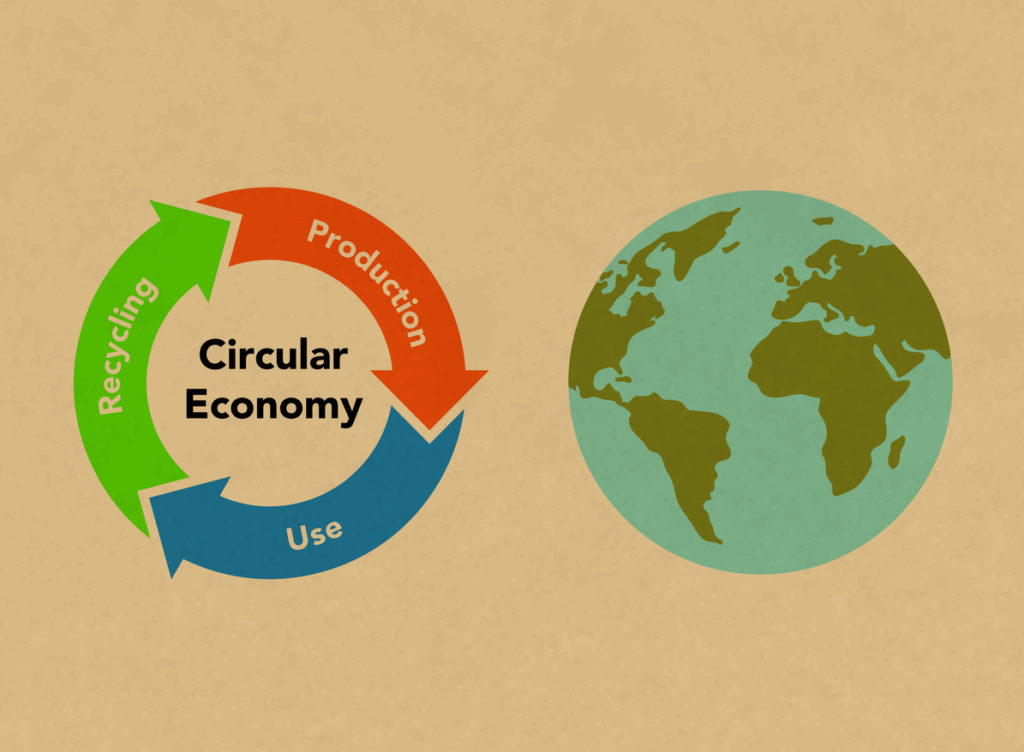

According to the Guardian a linear economy makes, uses and disposes materials. The circular economy looks at all the options across the chain to use as few resources as possible in the first place, keep resources in circulation for as long as possible, extract the maximum value from them while in use, then recover and regenerate products at the end of service life.

The Ellen MacArthur Foundation, whose mission is to accelerate the transition to a circular economy, asserts that the circular economy looks beyond the take-make-waste extractive industrial model and aims to redefine growth focused on positive society-wide benefits. It entails gradually decoupling economic activity from the consumption of finite resources and designing waste out of the system. Underpinned by a transition to renewable energy sources, the circular model builds economic, natural, and social capital and is based on three principles:

1. Design out waste and pollution. This is largely a result of the way we design products. Waste and pollution are not accidents. It is the consequence of decisions made at the design stage. By changing our mindset to view waste as a design flaw and harnessing new materials and technologies, we can ensure that waste and pollution are not created in the first place.

2. Keep products and materials in use. What if we could build an economy that uses products more like a service? By designing to keep products and materials in the economy, items can be reused, repaired, and remanufactured.

3. Regenerate natural systems. What if we could not only protect, but actively improve the environment? In nature, there is no waste. Everything is food for something else—a leaf that falls from a tree feeds the forest. Instead of simply trying to do less harm, we should aim to do good. By returning valuable nutrients to the soil and other ecosystems, we can enhance our natural resources.

The Ellen MacArthur Foundation illustrates the continuous flow of technical and biological materials through the ‘value circle’ known as The Butterfly Effect.

At Goodwill of San Francisco, San Mateo and Marin Counties (SF Goodwill), we are—and have been—working within the circular economy for 104 years. Based on the Ellen MacArthur Butterfly diagram, Goodwill contributes substantially in collecting, sharing, reusing, recycling, prolonging, maintaining, and redistributing goods—from fashion, to home goods, hardware, and more. Goodwill Industries overall operates more than 3,200 stores where used clothing can be donated. Such donations are the first part of a multi-step process aimed at finding ways to keep textiles out of landfills.

SF Goodwill sat down with Annie Gullingsrud, Chief Strategy Officer with EON and author, Fashion Fibers: Designing for Sustainability about her role on the SF Goodwill board and her passion about circular fashion. Annie brings her strong experience with circular fashion, systems, and materials to the board of SF Goodwill and we are so grateful for her insight, strategy, and knowledge.

Where does circular fashion sit in the circular economy model?

The circular economy is a new way to design, make, and use things within planetary boundaries. Shifting the system involves everyone and everything: businesses, governments, and individuals; our cities, our products, and our jobs. By designing out waste and pollution, keeping products and materials in use, and regenerating natural systems we can reinvent everything. Circular fashion is an approach that when successfully orchestrated, could ensure the future of our planet and all living things. This approach supports the development of safe, sustainable materials, clean production and energy, fair labor and continuous product and material loops through reuse, refurbishing, and recycling back to virgin quality materials that go into new fashion.

Can you tell us a bit about your work within the circular fashion industry? And what role, in your opinion, do you think Goodwill plays in the overall discussion of circular economy? And more specifically, how do you think Goodwill makes the fashion industry more sustainable?

The fashion industry has begun the shift toward the Circular Economy, incorporating innovation and new business models to ensure the continuous use and reuse of products and materials to reduce waste and resource consumption. But unless brands, retailers and their value chain partners—from resellers, renters, recyclers and more— can access essential information about products, it will be impossible to operationalize circular economy at the scale needed to create the business incentives and impact critical to making the shift.

Eon is bringing the circular economy online—digitizing products and enabling products to communicate, access and exchange data in the circular economy. Eon’s Internet of Things platform turns simple products into intelligent assets—pioneering the digital foundation of a connected and circular fashion and retail industry. I am excited to be a leader in a company that creates systemic, impactful change for the planet.

It is very clear to me that Goodwill is a leader in the circular economy too, which is why I am thrilled to be on the Board. I view Goodwill as the original circular business partner for brands. Goodwill gives clothes and products an opportunity to be utilized to its highest potential—which is a critical principle of the circular economy. As we know, Goodwill is incentivized by keeping garments at their maximum use and quality by keeping products circulating as much as possible in their original form. Goodwill’s emphasis is on resale —which takes far less resources than recycling.

A last resort should be recycling. But recycling technologies today are usually insufficient and cannot handle the diverse range of materials in our products—and our fashion. Developing new recycling techniques for blended garments and mixed materials is essential to being able to get some of these resources back in our supply chains.

My favorite part about Goodwill—and one I believe brands should really pay attention to—is Goodwill’s core mission of providing work to those that need second chances. So, everything that Goodwill does is in support of a higher purpose—while doing good for the environment.

How does this work with concepts like cradle to cradle that you hear mentioned in the same breath?

Essentially, most of these “economies” are about keeping products in circulation—at their highest and best use—in order to maximize a product’s utility and prevent waste of resources (including money). The planet cannot regenerate resources as quickly as we are taking them. We are not being responsible with those resources. Most of the products today—including packaging—end up going to the trash, sometimes minutes after use. Putting the environmental piece aside, this is just bad business. The vision is to essentially find new revenue generating activities from continuous use of resources, which is great for business. And ultimately our planet.

Our Interconnected Planet

There is an interconnected positive impact happening here—sustainable, environmental—that supports the mission of Goodwill, which in turn supports the positive impact in the world we are trying to stabilize and maintain.

If we are living responsibly in the world as humans, we must remember that we are borrowing resources from the world. We do not have infinite resources and we all have to remember this. If we send something into the world, we have to think of how to bring it back.

As fashion comes to grips with its own culpability in the climate crisis, the concept of upcycling, whether remaking old clothes or re-engineering used fabric or simply using what would otherwise be tossed into landfill, has begun to trickle out to various layers of the fashion world.